Insider Blows Whistle & Exec Reveals Google Plan to Prevent “Trump situation” in 2020 on Hidden Cam

BIG UPDATE: YouTube has REMOVED the video from their platform. The video is still available on this website page.

UPDATE 1: Congressman Louie Gohmert issued a statement, saying “Google should not be deciding whether content is important or trivial and they most assuredly should not be meddling in our election process. They need their immunity stripped…”

UPDATE 2: Google executive Jen Gennai RESPONDED to the video, saying, “I was having a casual chat with someone at a restaurant and used some imprecise language. Project Veritas got me. Well done.”

Insider: Google “is bent on never letting somebody like Donald Trump come to power again.”

Google Head of Responsible Innovation Says Elizabeth Warren “misguided” on “breaking up Google”

Google Exec Says Don’t Break Us Up: “smaller companies don’t have the resources” to “prevent next Trump situation”

Insider Says PragerU And Dave Rubin Content Suppressed, Targeted As “Right-Wing”

LEAKED Documents Highlight “Machine Learning Fairness” and Google’s Practices to Make Search Results “fair and equitable”

Documents Appear to Show “Editorial” Policies That Determine How Google Publishes News

Insider: Google Violates “letter of the law” and “spirit of the law” on Section 230

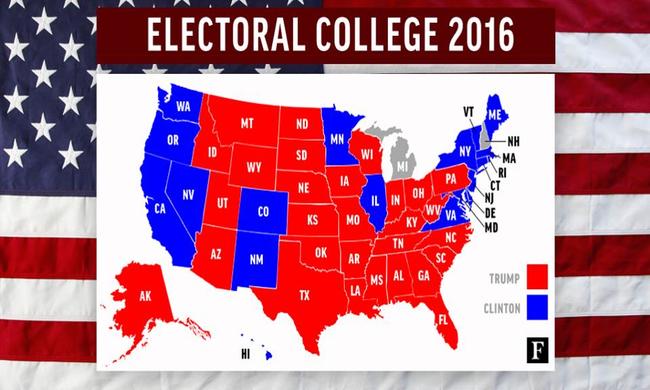

(New York City) — Project Veritas has released a new report on Google which includes undercover video of a Senior Google Executive, leaked documents, and testimony from a Google insider. The report appears to show Google’s plans to affect the outcome of the 2020 elections and “prevent” the next “Trump situation.”

The report includes undercover footage of longtime Google employee and Head of Responsible Innovation, Jen Gennai saying:

“Elizabeth Warren is saying we should break up Google. And like, I love her but she’s very misguided, like that will not make it better it will make it worse, because all these smaller companies who don’t have the same resources that we do will be charged with preventing the next Trump situation, it’s like a small company cannot do that.”

Said Project Veritas founder James O’Keefe:

“This is the third tech insider who has bravely stepped forward to expose the secrets of Silicon Valley. These new documents, supported by undercover video, raise questions of Google’s neutrality and the role they see themselves fulfilling in the 2020 elections.”Jen Gennai is the head of “Responsible Innovation” for Google, a sector that monitors and evaluates the responsible implementation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies. In the video, Gennai says Google has been working diligently to “prevent” the results of the 2016 election from repeating in 2020:

“We all got screwed over in 2016, again it wasn’t just us, it was, the people got screwed over, the news media got screwed over, like, everybody got screwed over so we’re rapidly been like, what happened there and how do we prevent it from happening again.”

“We’re also training our algorithms, like, if 2016 happened again, would we have, would the outcome be different?”

Google: Artificial Intelligence Is For A “fair and equitable” State

According to the insider, Machine Learning Fairness is one of the many tools Google uses to promote a political agenda. Documents leaked by a Google informant elaborate on Machine Learning Fairness and the “algorithmic unfairness” that AI product intervention aims to solve:The insider showed Google search examples that show Machine Learning Fairness in action.

“The reason we launched our A.I. principles is because people were not putting that line in the sand, that they were not saying what’s fair and what’s equitable so we’re like, well we are a big company, we’re going to say it.” – Jen Gennai, Head Of Responsible Innovation, Google

The Google insider explained the impact of artificial intelligence and Machine Learning Fairness:“They’re going to redefine a reality based on what they think is fair and based upon what they want, and what and is part of their agenda.”

Determining credible news and an editorial agenda. . .

Additional leaked documents detail how Google defines and prioritizes content from different news publishers and how its products feature that content. One document, called the “Fake News-letter” explains Google’s goal to have a “single point of truth” across their products.Another document received by Project Veritas explains the “News Ecosystem” which mentions “editorial guidelines” that appear to be determined and administered internally by Google. These guidelines control how content is distributed and displayed on their site.

The leaked documents appear to show that Google makes news decisions about what news they promote and distribute on their site.

Comments made by Gennai raise similar questions. In a conversation with Veritas journalists, Gennai explains that “conservative sources” and “credible sources” don’t always coincide according to Google’s editorial practices.

The insider shed additional light on how YouTube demotes content from influencers like Dave Rubin and Tim Pool:“We have gotten accusations of around fairness is that we’re unfair to conservatives because we’re choosing what we find as credible news sources and those sources don’t necessarily overlap with conservative sources …”

“What YouTube did is they changed the results of the recommendation engine. And so what the recommendation engine is it tries to do, is it tries to say, well, if you like A, then you’re probably going to like B. So content that is similar to Dave Rubin or Tim Pool, instead of listing Dave Rubin or Tim Pool as people that you might like, what they’re doing is that they’re trying to suggest different, different news outlets, for example, like CNN, or MSNBC, or these left leaning political outlets.”

Internal Google Document: “People Like Us Are Programmed”

An additional document Project Veritas obtained, titled “Fair is Not the Default” says “People (like us) are programmed” after the results of machine learning fairness. The document describes how “unconscious bias” and algorithms interact.Veritas is the “Only Way”

Said the insider:“The reason why I came to Project Veritas is that you’re the only one I trust to be able to be a real investigative journalist. Investigative journalist is a dead career option, but somehow, you’ve been able to make it work. And because of that I came to Project Veritas because I knew that this was the only way that this story would be able to get out to the public.”Project Veritas intends to continue investigating abuses in big tech companies and encourages more Silicon Valley insiders to share their stories through their Be Brave campaign.

“I mean, this is a behemoth, this is a Goliath, I am but a David trying to say that the emperor has no clothes. And, um, being a small little ant I can be crushed, and I am aware of that. But, this is something that is bigger than me, this is something that needs to be said to the American public.”

As of publishing, Google did not respond to Project Veritas’ request for comment. Additional leaked Google documents can be viewed HERE.

Other insider investigations can be viewed here: